|

Shipbuilding, or more accurately boatbuilding, has been carried out on the Tyne for millennia but those early days are not recorded anywhere.

In fact, the earliest recorded launch was in 1294 when a galley was launched into the Lort Burn for King Edward I.

The Lort Burn still exists but is now in a culvert under Dean Street in Newcastle.

At the time of the launch the Lort Burn was tidal and navigable for some way towards what is now Grey Street.

King Edward’s galley was 135ft long and cost £205. The coal trade The driving force for shipbuilding was coal. The coastal transportation of coal had its roots in the Middle Ages, if not before. By 1592, 91,420 tons of coal were exported from the Tyne, coastwise, in that year and in the following year this increased to over 1000,000 tons. By 1800 coal exports had increased to 1,425,151 tons and by 1820 it was past the 2,000,000 tons mark. To give some idea of how many ships were involved in this trade it is interesting to see an item in the Newcastle Courant for 09/01/1830 which reported that 72 colliers had cleared the Tyne in the previous week. By the end of the year 11,226 colliers carried away 2,167, 355 tons of coal. In the early days very little of this coal would have been carried in Tyne built ships. Home trade ships were predominantly from Ipswich or Kings Lynn and foreign trade was carried in Dutch or French ships. But by 1730 this was starting to change, with more cargoes being carried in British ships and with an increasing number built on the Tyne. There were two main constraints to the development of shipbuilding on the Tyne, the Guilds and the River Tyne itself. The Guilds The Guilds or Freemen of Newcastle controlled where shipbuilding could take place. Henry I (1069 to 1135) granted Newcastle a virtual monopoly of all trade on, to or from the River Tyne. It was therefore decreed that none but freemen of Newcastle and members of the Shipwrights Guild could build ships on the Tyne, and that no vessel should be constructed at Shields, North or South. This was further endorsed in a statement by the Shipwrights Company in 1673 that stated that no freeman shall live at North Shields or South Shields to work as a shipwright without licence from the wardens and Society. From time to time this monopoly would be tested by North Shields, backed by the Prior of Tynemouth and by South Shields, backed by the Bishop of Durham. However this monopoly continued to be maintained, often by force, until about 1720. Robert Wallis of South Shields is often quoted as the shipbuilder who finally broke this monopoly, but his battle was probably the most public in a series of actions. The River The River Tyne today is very different from what it was just 200 years ago. Today it is wide and deep, even though serious dredging ceased in about 1990, whereas in the early 19th century it was shallow, with islands, sand banks, tight bends and generally not conducive to navigation. In 1774 it was said that the Tyne Conservancy Board had allowed the river to be, from ignorance , inattention and avarice, converted into a cursed horsepond.

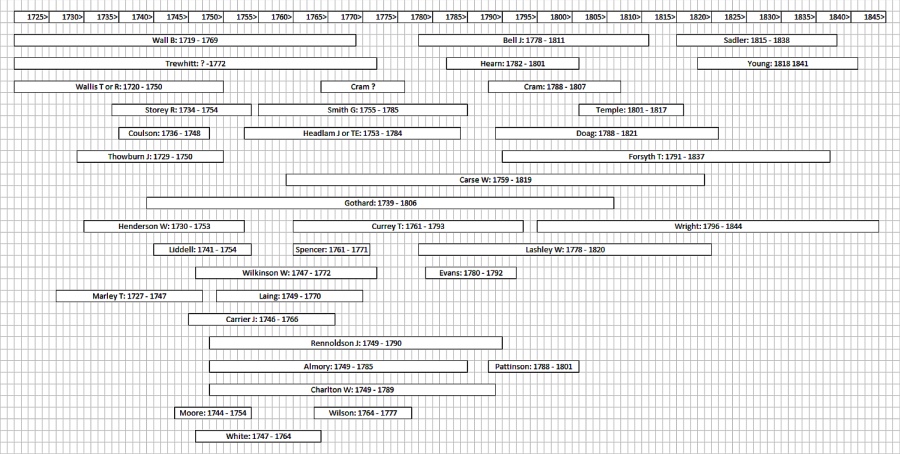

Above map, dated 1670, is copyright of Tyne & Wear Museums. CLICK to enlarge/BACK to return The Tyne at Newcastle was very narrow and flowed between steep banks with limited space for shipbuilding yards on the riverside. Some freemen therefore opened yards nearer to the mouth of the river, not at Shields but at Howdon instead. In the mid-1800s the Tyne was also a dangerous river to get in and out of. The North and South Piers were not completed until 1895 and before then there was a constantly shifting bank of shingle and sand over a rocky base that formed a bar across the river mouth. Safe navigation into or out of the river depended on the draft of the vessel, the tide and the prevailing wind. Many ships were wrecked when making to enter or leave the river. If the prevailing wind was from the East, then the river mouth became even more dangerous as steep waves and spray made the entrance almost impassable. Therefore, movement in and out of the river was entirely dependent on the weather. For example, a prolonged period of Easterly winds in the winter of 1847 penned over 1,700 sailing vessels in the river and on the day that the winds dropped, and the sea state improved, some 400 vessels left the river on the same tide.Early yards The earliest shipbuilding yards were at the Close Gate or the North Shore at Newcastle itself but in about 1665 new slipways were added at St Lawrence. In 1685 Parliament passed an Act to penalise the use of foreign tonnage and encourage British shipbuilding and this provided a short-term lift for the Newcastle yards, but by 1722 some Tyne skippers were quoted as saying "Shipbuilding had formerly flourished at Newcastle". Small wooden cargo ships called Keels were used to move coal on the River Tyne, taking loose coal from the upriver pits to the river mouth where the coal was loaded onto larger seagoing vessels. Keels carried about 21 tons of coal, but they were not seaworthy craft, especially when fully loaded. It is estimated that there were probably 200 to 300 keels on the river in 1655. Most of these would have been constructed locally and this number had grown to some 400 by 1725. Shipyards as such were not necessary for keel building, a strip of riverbank or beach from which the vessel could be launched into the river was all that was needed. There was no requirement for permanent buildings of any sort, or equipment such as cranes for lifting heavy weights. Prominent shipwrights building at Newcastle in the 17th century were Greene, Steel, Wilkinson and Wrangham. A 1778 Newcastle Directory lists, George Cram, Thomas Curry & William Lashley building at the Mushroom. On the North Shore, William Carse, Walter Middlemas & William Charlton. On the South Shore, John Summers, Thomas Emmerson Headlam & John Rennison (Rennoldson). The following chart of shipbuilders was produced by JF Clarke & is an analsis of the shipwrights active on the Tyne between 1725 & 1845 and makes an assumtion that a shipwright with 3 or more apprentices was likely to be a shipbuilder in his own right. An apprentice was enrolled with his shipright master for a period of seven years.

Above chart identifies shipbuilders between 1725 & 1845. CLICK to enlarge/BACK to return The coming of steamThe Tyne didn't have a monopoly of supplying London coal, there were many other coalfields in the country eager to sell their coal there as well. The key factor was price, that is the lower the price of the coal in London, the more likely it was to sell. So getting coal to London as cheaply as possible was the name of the game. Before 1840 or thereabouts, the competition was from other sailing vessels coming from Kent, South Wales and even Scotland, but then came the railways. The development of the railway system made it possible for coal mined in the Midlands to be brought to London. It began in earnest in 1845 when 8,000 tons reached the capital in this way, but then this increased to 38,000 tons in 1848 and 248,000 tons in 1851. There was even talk of bringing coal from the Tyne to the Thames by rail. The big advantage that rail transport provided was reliability. Railways were more expensive but supplies could be guaranteed. The sailing collier on the other hand was dependent on the vagaries of the wind and weather. The wind and weather were the key factors that governed the productivity of sailing colliers. If the winds were from the north then a trip to London was straightforward and relatively swift but the return journey could be a nightmare. Often sailing vessels would tack across to the other side of the North Sea, near Belgium or Holland, to try and gain a few miles of northern movement only for the opposite tack to bring them back to their starting point, or even worse some miles further south. The introduction of steam tugs on the Tyne, from 1815 onwards was to be of immense value to the sailing ship owners. Navigation up and down the Tyne was much improved with a steam tug. A steam tug could bring a vessel into or out of the Tyne against the wind and steam tugs would often go as far south as the Humber to pick up sailing ships that were struggling to get to the Tyne because of the opposing winds. It is estimated that sail powered colliers would make 8 round trips to London every year, however with the assistance of steam tugs 13 such voyages were then possible. Many of these steam tugs were built on the Tyne and a thriving marine engineering business grew up to support this new industry. However all this inventiveness only served to delay the inevitable impact of the competition from the railways. The stean collier What was required to combat the onslaught of the railways, was first outlined in January of 1845 in the provisional registration of a new company, the General Steam Collier Company. The company was being formed " . . . to carry coals by steam colliers constructed to take large cargoes with light draught of water which will make their passages regularly throughout the yearensuring a supply at moderate prices." In fact this company seems to have foundered before being able to put its proposals to the test. However 7 years later a similar company the General Iron Screw Collier Company did debut the iron steam collier and changes in the carriage of sea borne coal really got under weigh. The first true steam cpllier built for the London trade was the JOHN BOWES built by Palmers in 1852. She cost £1000 to build which was 10 times the cost of a sailing brig. But she carried as much coal on a round trip to London of 5 days as the brig would carry in 2 months. The JOHN BOWES was to be followed by a steady stream of similar vessels. Customs Registration In 1786 all British ships were required by law to register at a Customs port. This was the begining of accurate records regarding place of build, dimensions and ownership of all seagoing vessels. TO BE CONTINUED |